[Editorial] They’re Coming to Re-Invent You, Barbara! Night of the Living Dead 1968 vs Night of the Living Dead 1990

Spoilers Ahead for Night of the Living Dead 1968 /1990

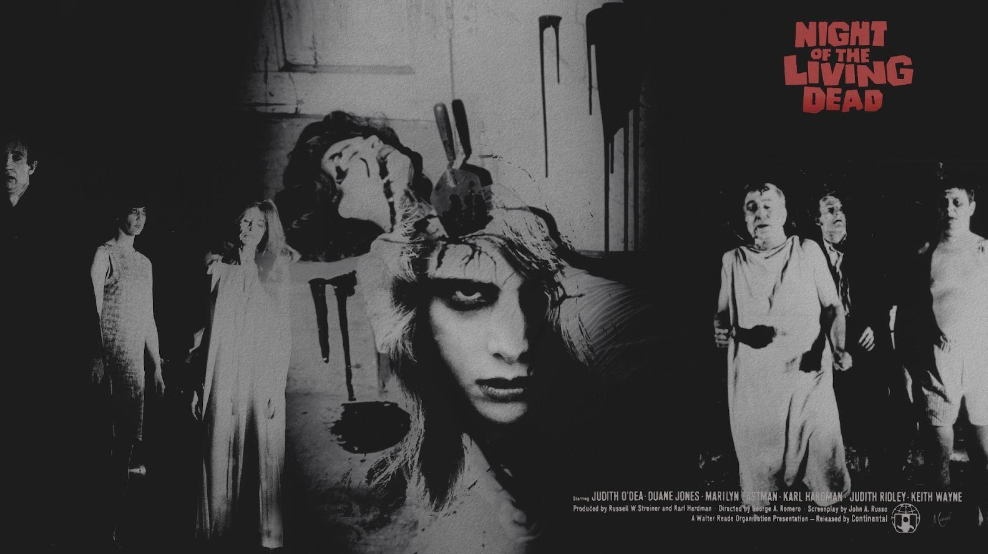

The year was 1968 and a young man named George A. Romero had shot his first film, a horror movie that would change the world of cinema and not just horror cinema, at that. Night of the Living Dead (1968), would go on to become one of the most important and famous horror films of all time as it tackled not only survival horror but also very taboo and shocking topics like cannibalism and matricide.

Through a serendipitous twist, the social commentary that Romero would become known for as his career progressed (particularly on race in the case of Night of the Living Dead) came at a time when the Civil Rights movement in the United States was evolving radically. By casting Duane Jones, a Black man, as the main character of Ben who was a headstrong, intelligent, and mostly-magnanimous leader for the combative group of survivors in a rural Pennsylvania farm house near the town cemetery, Romero changed history and challenged roles and tropes in horror films for Black characters.

The role of Ben was not written to be portrayed by a Black man and, therefore, his race is never addressed and this makes the role and the grand finale come across all the more intensely. Romero and his co-writer, John Russo, penned a daring and bleak script but Romero cast Duane Jones as the hero because he was simply the best actor who auditioned. The result was lightning in a bottle. Jones’ portrayal of the heroic and doomed Ben is nearly untouchable, practically making it impossible for anyone to ever attempt to recast the character, though Tom Savini, director of Night of the Living Dead (1990), would be tasked to do so decades later.

In 1968, the year of the original Night of the Living Dead’s release, an unthinkable tragedy happened on April 4th with the assassination of Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee. He was fatally shot with a sniper bullet by James Earl Ray. This senseless act of violence of a white man killing a powerful Black man resonated with audiences as we see our hero Ben in Night of the Living Dead (1968) become the sole survivor of one of the longest nights in horror history who, upon hearing rescue coming, emerges from hiding only to be gunned down by a mob of white men with a death by a sniper’s bullet and leaves horror fans with one of the bleakest endings in horror history.

It is important to note that the film begins with the focus on the character of Barbra, a white woman, and her brother heading out to the cemetery in a rural area to put a wreath on their father’s grave. Barbra, upon escaping zombies (simply called “ghouls” in the film) in the cemetery, meets Ben and the two begin their survival journey together in the farmhouse. Barbra becomes hysterical and then catatonic with Ben actually striking Barbra to calm her down at one point. The issue with certain audiences at the time was not about a man striking a woman, but with a Black man striking a white woman. Barbra (Judith O’Dea) quickly becomes the catatonic and dissociative background character in the film until her unexpected and, frankly, ironic death. Romero would come to greatly regret writing the character of Barbra this way. He took it upon himself to correct this when Tom Savini, directing his first film with Night of the Living Dead (1990), worked with Romero’s own updated script for the remake of his classic film.

A final note on Night of the Living Dead (1968) comes from the words of master horror novelist Stephen King, as taken from his 1981 non-fiction horror media retrospective Danse Macabre: “The good horror director must have a clear sense of where the taboo line lies, if he is not to lapse into unconscious absurdity, and a gut understanding of what the countryside is like on the far side of it. In Night of the Living Dead, George Romero plays a number of instruments, and he plays them like a virtuoso. A lot has been made of this film’s graphic violence, but one of the most frightening moments comes near the climax, when [Barbra’s] brother makes a reappearance, still wearing his driving gloves and clutching for his sister with the idiotic, implacable single-mindedness of the hungry dead. The film is violent [...] - but the violence has its own logic, and I submit to you that in the horror genre, logic goes a long way toward proving morality.” (King, Stephen. Danse Macabre. New York: Berkeley, 1981. Print.)

As far as remakes go, particularly in the horror genre, fans can be bloodthirsty and unforgiving and so very few are given audience approval because many fans believe that one cannot surpass the original. I, personally, believe that - if done well - a remake does not need to surpass the original, just merely hold its own in a brilliantly unique way. With Night of the Living Dead (1990), there were many odds in the film’s favor: Tom Savini, a veteran member of Romero’s inner circle with his legendary special effects and stunt work and acting in Romero’s films, was directing the new script written by George A. Romero himself with much more money available to update the film from its low budget roots and, yet, the challenges were enormous, particularly in having to cast such an important role as that of Ben, and Savini has gone on record many times in expressing how awful of an experience he had directing the film due to the film being rejected by the MPAA and cut and recut several times. The most important thing to remember about the legacy of Night of the Living Dead (1990) as it pertains to Tom Savini’s bitterness is that the film was not received well by audiences and bombed at the box office and Savini took it very much to heart.

In updating his own original film and script, Romero wanted very much to reassess the climate of the original Night of the Living Dead, meaning that the character of Barbara (spelling change for the 1990 film) had to change. Romero had more of his “Dead” films under his belt by this time (Dawn of the Dead 1978 and Day of the Dead 1985) and his evolution as a horror director who dealt with important human threats and social issues pushed him to re-invent Barbara (Patricia Tallman) as a character who rises up in strength and doesn’t fade away to the background but instead stands up to fight and becomes the strongest of the group trapped while the undead attack and, ultimately, the heroine. With such a dramatic shift in Barbara’s character, it was inevitable that the character of Ben (Tony Todd) be also rewritten from being the wise and calm hero to a troubled hero who gives in to his anger and turmoil with the human antagonist, Harry Cooper (Tom Towles), resulting in a very different bleak ending from the 1968 film.

I find Night of the Living Dead (1990) to be one of horror’s more superior remakes. The updates are perfect, as they should be with Romero working with his own concept. Barbara and Ben are an amazing power duo and it gives a fresh feeling to what had become a trope by 1990 with the zombie film - a remake of the birth of the trope, the attempt to make it feel fresh and relevant and to prove that things can change and that change can be a good thing. The perfection of the immensely-talented Tony Todd in a pre-Candyman (1992) dramatic role cannot even be disputed. No one could stand in the legendary Duane Jones’ shoes, but Tony Todd comes as close as humanly possible. I stand firm that the ending of Night of the Living Dead (1990) holds a lot of weight and gravitas akin to the original film without succumbing to the easiest route of getting there. I am pleased that this 1990 remake is having its renaissance and getting its due credit to all involved in the film. My horror podcast, The House That Screams, covered it early in our three and a half years of the show and it was our most-downloaded episode for nearly 2 years. It proved to me that people want to hear about and discuss this neglected remake. I try not to spoil the ending for Night of the Living Dead (1990) because too many people either dismissed it at the time of the film’s release 33 years ago or they simply haven’t seen the film. I urge these people to seek out the film as it regularly is on streaming services and to really have a fresh perspective on the work.

A final note on Night of the Living Dead (1990) from Bloody Disgusting.com: “Since 1990, George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) has been reworked, remade, re-cut, and re-imagined in various cinematic mediums by myriad filmmakers, but the only re-imagining that’s come close to the original is Tom Savini’s Night of the Living Dead (1990). It’s a classic in its own right that continues to win over a new fan base for its bold and creative re-imagining of what is arguably the perfect horror film. You can’t top perfection. But it’s hard to imagine anyone doing it better than Savini did.” (Velasquez Jr., Felix. “Tom Savini’s ‘Night of the Living Dead’ Remains One of the Great Updates of a Classic Horror Film.” BloodyDisgusting.com, 4 December 2014).

I’ve had the pleasure of recording episodes on my podcast covering both versions of Night of the Living Dead.

![[Editorial] “I control my life, not you!”: Living with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and the catharsis of the Final Destination franchise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696444478023-O3UXJCSZ4STJOH61TKNG/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.30.37.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)