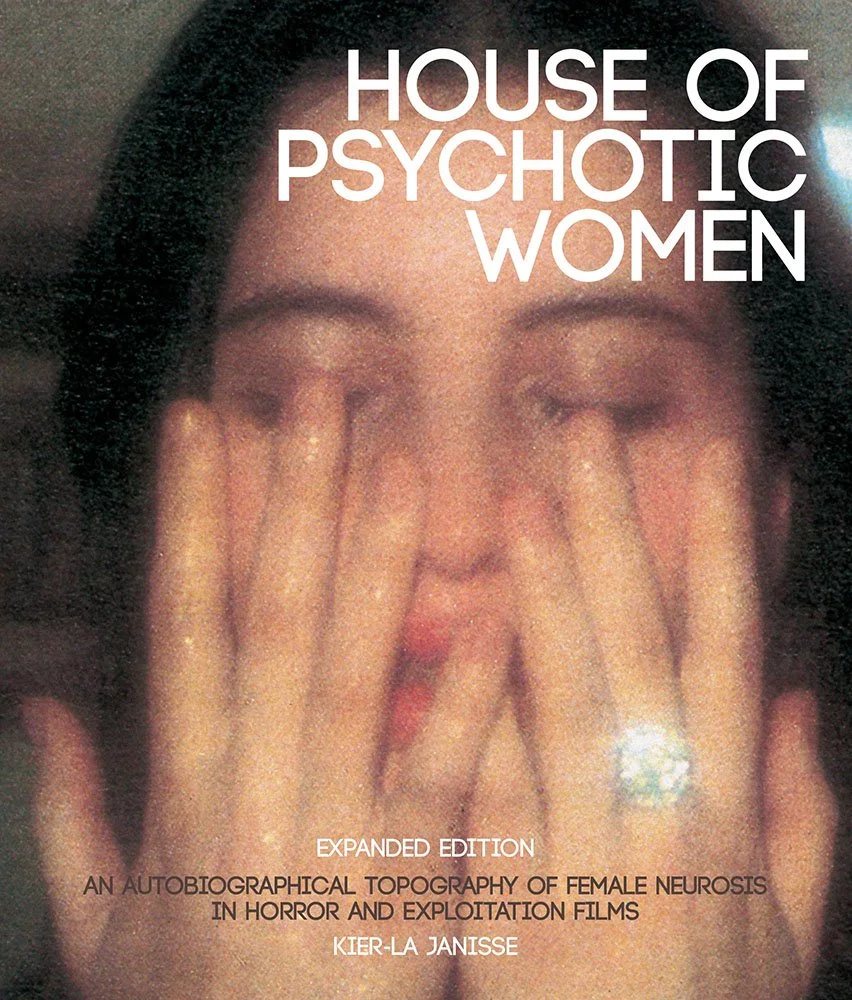

[Book Review] House of Psychotic Women

House of Psychotic Women: An autobiographical topography of female neurosis in horror and exploitation films by Kier-La Janisse

House of Psychotic Women is a fascinating beast. Part autobiography, part reference book, it is a love letter to the topic of female neurosis from author Kier-La Janisse. The notion of female neurosis is an area ripe for exploration, given its consistent social and cultural ramifications and its unending presence in the horror and exploitation genres and so, there is a lot of fruit to pluck from this particularly twisted tree.

In spite of this breadth, Janisse has managed to formulate the narrative in such a way that it is readily accessible and enables the reader to return to their preferred area of interest at will. This alone makes House of Psychotic Women a vital resource for anyone interested in reading (and writing) about horror. As a horror scholar myself, I find the accessibility of this book to be one of its most redeeming qualities alongside the range of films covered and the depth of Janisse’s clear knowledge of the films explored.

House of Psychotic Women also serves as a comprehensive introduction to the topic of female neurosis within both horror and exploitation, lending itself to both those with pre-existing knowledge and those just starting out. Janisse’s discussion about the films contained within this work are both approachable to someone new to film analysis, and in-depth enough for those looking to build on their existing knowledge.

Due to my own love for complicated women and horror, I have seen a number of the films that Janisse covers. It is remarkable to see how someone I have never met can give such a clear voice to my own thoughts on some of these characters. A notable example is Erika in The Piano Teacher, a woman driven to be freed from her life, to drop a bomb and watch her world shatter into smithereens. This manifests as a deep desire to show weakness, to be debased and abused, violated and adored. Through her increasingly extreme acts of perversion, as perceived by those around her, she seeks to find a love that can transcend the boundaries of the life she so carefully controls. Even in her quest for weakness, she is still the one pulling the strings, as Janisse notes “…she wants to determine the form of submission herself”. Janisse’s reading of Erika is full of compassion, and highlights the similarities drawn between the author and the character’s experiences. It is this recognition of these similarities that separates House of Psychotic Women from other similar works and gives real depth to Janisse’s writing. Peppered throughout the chapters are personal anecdotes from Janisse’s life and these intimate expressions of vulnerability add a powerful layer of realism to the analysis of the films that follow. It is apparent that Janisse, like many women who love horror, has found a sense of belonging and comfort in these women who engage in ‘unpalatable’ behaviours, who refuse to conform to the rigid expectations of society.

As well as giving form to my thoughts about characters from films I have already seen, House of Psychotic Women has also provided me with an extensive to-watch list, that could keep me busy for years. It’s also encouraged me to watch films that I may have skipped over and introduced me to some new favourites. One of these is Possession, an often misunderstood piece that centres on the delightfully abstract and hard to define character of Anna. This film has many intricacies and complexities that

have often been detrimentally received by reviewers. This intricate complexity is never more apparent than in Anna herself, who is a woman as divided as the city of Berlin that she inhabits, expressing this tension in increasingly violent and disturbing ways. Janisse’s discussion about Possession takes into account not only the story itself, but also its wider production. This approach again adds an extra level of insightfulness to House of Psychotic Women, and highlights how meticulously and lovingly Janisse has researched these films.

There is also the thrilling notion that these women, with their transgressive, difficult, often ugly and perverse desires and behaviour, are more liberated than most could ever be. Through the very act of transgression, we are free. Whilst many of the women who transgress these moral, social and criminal boundaries are punished, in a myriad of ways, they are still freed from the shackles of being ‘proper’, liberated from the boredom of conformity and have the chance to exist unrestrained and uncontained by anyone’s rules but their own. Although the consequences for some may be dire, isn’t it worth it to be autonomous and self-determining? To live with unrestrained abandon? Many of the characters explored in this book find themselves, over the course of the film that contains them, trapped in a cage. And much like a captive bird that escapes through an open window, only to die in the wild outdoors it cannot comprehend, these women sacrifice everything, even their own life, for a taste of the fresh air of absolute freedom. In Janisse’s hands, these narratives do not feel like cautionary tales of what happens to women who disobey social expectations, but instead feel full of power. It is refreshing to see a book about women in horror that takes this approach and I wouldn’t be without my copy. Read it, and see for yourself.

![[Book Review] Wylding Hall (2015)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484930026-PFRK7O26SLME4JIC49EW/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.59.04.png)

![[Book Review] Penance (2023) by Eliza Clark](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695481011772-L4DNTNPSHLG2BQ69CZC1/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.54.07.png)

![[Book Review] The Exorcist Legacy: 50 Years of Fear](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328003764-IASXC6UJB2B3JCDQUVGP/61q9oHE0ddL._AC_UF1000%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Nineteen Claws And A Black Bird (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685872305328-UE9QXAELX0P9YLROCOJU/62919399._UY630_SR1200%2C630_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Manhunt (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1683911513884-1Q1IGIU9O5X5BTLBXHV9/53329296._UY630_SR1200%2C630_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Eyes Guts Throat Bones (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682344253308-4AAFX12YD84EVJBYNJBZ/7e617654-8d9e-407e-8cde-33a97df84dcf.__CR0%2C0%2C970%2C600_PT0_SX970_V1___.jpg)

![[Book Review] Cursed Bunny (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1680266256479-2E2XJT4T8CGAMOUB7XAL/298618053_5552736738082400_5168089788506882676_n.jpg)

![[Book Review] The Aosawa Murders (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678009096264-7QOOFO5PI9LAX47L3GF6/51054767.jpg)

![[Book Review] Hear Us Scream Vol II](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667055587557-4AIJTAG4N5VUZE8AC0SF/FrontCoverMarinaCollings.png)

![[Film Review] Return to Silent Hill (2026)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769672582439-C8RQWP3CYUW1JX4ZRNLE/RETURN+TO+SILENT+HILL.jpg)

![[Film Review] Flights of Reverie (2025)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769111579457-CTUW03G3J34P6SFRWWEM/flights-of-reverie-filmstill-ornithologist-berlin-li-wallis06.jpg)

![[Film Review] Confessions in Static (2025)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1768397467245-3KOF3LUBRDQVJ8QVDONA/Confessions_Key_Alternate_1920x1080.png)

![[Film Review] Stalker (2025)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1768232505839-TS9K7YBLOXNQML8PUWTP/Screenshot+2026-01-12+at+15.17.49.png)

![[Film Review] Bone Lake (2025)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1768151214859-U1AUN7JALKRK4W5NGJVH/Andra+Nechita+and+Maddie+Hasson+in+Bone+Lake+%28Signature+Entertainment%29+1.jpg)

![[Film Review] 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple (2026)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1768152692285-7TK6SN62JY4H3TJDYABP/The+Bone+temple.jpg)

![[Film Review] Pelverata (2025)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1767549668681-1TW6BD7QQHK8WS8L4IVT/Screenshot+2026-01-04+at+17.57.01.png)

![[Film Review] A study of the human ability to endure self-inflicted pain in XXXDarknet: Red Lips](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1767542371615-YUJBD442MS9NAGEB45D7/redlips.jpg)

Happily, her new anthology The Book of Queer Saints Volume II is being released this October. With this new collection, queer horror takes center stage.