[Editorial] I’m Your No.1 Fan: Closets, Mazes & Burning Books - How Carrie, The Shining & Misery Soothe my Anxiety

Feeling trapped and alone are common fears I face every day as an anxiety sufferer. Existing in a world which has in the last few years seen a global pandemic and a widespread shift to the political right has only served to heighten this. The works of Stephen King explore some of the most personal and unsettling themes that -for better or worse- I find myself searching for in horror.

The adaptations I turn to allow me to sit comfortably in discomfort, knowing that although I may experience feelings of alienation and anxiety, through horror I can experience this in extremes, making real-life situations seem much less daunting. The presentation of isolation and entrapment in Carrie, The Shining and Misery share similarities in their portrayals of loneliness and the impact that the environment has upon their characters. Some are tragic, some are redemptive, but they all offer hope and encourage me to remember that it is perfectly safe to allow my anxieties to be present without meaning they will overpower or define me.

Pushing Through the Dirt: Carrie (1976)

Carrie is a painfully real depiction of bullying and estrangement, making for an uncomfortable and unpleasant watch. As a teenage girl battling the struggles and trials of adolescence, Carrie finds herself in a chokehold everywhere she turns: from the privacy and safety of the domestic sphere through her tyrannical mother, to the public social setting amongst her peers. As someone who experienced bullying in high school, I identify with this sense of dread and detachment that is especially amplified as a teenager. Watching Carrie pivot between the two equally damaging and abusive environments of home and school, spaces which are devoid of compassion and acceptance, with her enveloping isolation striking an affecting chord.

Carrie’s position on the borders of social acceptability is immediately conveyed in the films’ opening credits where-she showers alone, evoking Marion Crane’s final moments in Hitchcock’s Psycho. Traditionally a symbol of purity in cinema, here the tiled cubicle also becomes a place of entrapment meaning that she is easily surrounded when attacked by her bullies. Naked and vulnerable, she is defenceless. The shower also acts as a foreshadowing reflection of the dark and confined closet that her mother banishes her to, invoking repeated instances of trauma. By sending her daughter to the closest, Margaret White attempts to contain Carrie’s power, a threat which she detects is fast emerging. A victim of torment and bullying at school, Carrie is further subjected to a life of suffocation and dictates through her fanatically religious mother at home. The regime of strict rules and regulations mean that Carrie is denied the freedom and happiness of a teenage life as she instead finds herself entrapped in the four walls of her house (which will eventually fall in on her for good in the film’s denouement) unable to cultivate a place for herself in the outside world.

The literal confines of the shower and the closest coupled with the psychological entrapment she is forced to endure is turned on its head when a humiliated Carrie post-prom becomes not the entrapped but the entrapper, locking the doors of the school hall to seek her revenge. Although she has found her inner power and unleashes carnage, she remains isolated, a single figure standing on the stage covered in blood. After exorcising her rage, Carrie arrives at the ultimate and final point of isolation and entrapment when she is killed as her house collapses on top of her in a moment reminiscent of another famous witch in cinema (the Witch of the East in The Wizard of Oz). Now in the ground and unable to move, Carrie is back in a secluded position of powerlessness. However, the final and famous jump scare where her hand reaches defiantly out of the rubble fills me with the optimistic belief that whatever life throws my way, my strength will allow me to push through the dirt.

Running Towards Love: The Shining (1980)

Wendy Torrance might be the most isolated woman in horror; not only is she without friends or family (outside of Jack and Danny) but she finds herself imprisoned in the empty confines of a hotel with a violent husband who is slowly unravelling before her eyes. Watching Wendy gives me power, it makes my heartbeat fast with fear while also filling me with confidence that I too, have the inner resources I need to pick myself up in times of high anxiety.

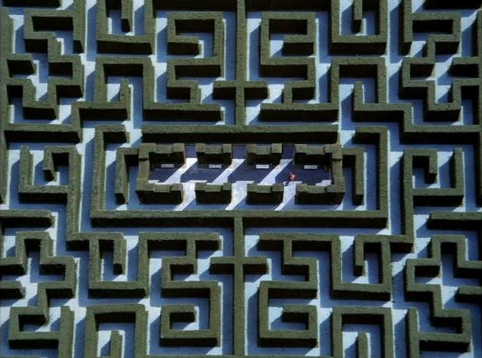

Although the Overlook Hotel is an endless labyrinthian space, the sense of claustrophobia is suffocating, particularly once the snow sets in and it becomes apparent that -despite being surrounded by nothing but space- Wendy literally has nowhere to run to. Kubrick is masterful at creating an atmosphere that swings on a pendulum of nervousness and dread, juxtaposing the grandness of the Colorado lounge with equally fear-inducing scenes in the tightness of the hotel’s corridors and hedge maze. While Jack transforms into an abusive and unpredictable killer, Wendy’s priority is to protect herself and their infant son, Danny.

As events escalate and Jack pursues her manically through the Overlook, Wendy seeks safety in the bathroom although this protects her and Danny temporarily, they are once again trapped as Jack hacks at the door with an axe. In a nerve-inducing scene, she displays her resilience and willingness for the survival of her son by pushing him through a small window, proving that in the most dire and dangerous of circumstances, there is always a way out to be found.

As Danny flees to the hedge maze, he is isolated in a mythological nightmare with Jack in close pursuit. By cleverly stepping backwards into his own footprints in the snow, Danny deceives his father and makes it out into the arms of Wendy before they escape in the snowcat. Life often feels like a hedge maze, with paths that lead to dead ends and without knowledge of if there are potential monsters waiting for us around every corner. But seeing Wendy and Danny escape recharges my spirit. Although I often feel trapped by my biggest monsters -my thoughts- The Shining teaches me not to allow my fears to haunt me and that-like Danny-I can feel safe in running towards love.

Learning to Live with Trauma: Misery (1990)

In Misery, writer Paul Sheldon finds himself in two situations of entrapment and danger; the first involves his car veering off the road during a snowstorm, leaving him unconscious and unable to move. Fortunately, he is rescued from the car by a woman named Annie Wilkes. Unfortunately, this escalates to his next situation of ensnarement - one which he will remain in for the majority of the film, as it transpires that Annie’s initial nurturing intentions are wrapped up in unhealthy obsessions and a deceptive personal history.

At the beginning of the film, we see Paul in talks with his agent, confessing feelings of unfulfillment in his career, a disclosure that highlights how the creative restrictions he is experiencing mirror the forthcoming physical limitations he will be placed under. As the number one fan of Paul’s Misery series, Annie admits to stalking the writer who she knows chooses to isolate himself at Silver Creek Lodge as part of his creative process. As such, isolation leads to entrapment with Paul confined to one bed and four walls amidst the remoteness of the Wilkes’ farm.

While Annie comes and goes, keeping from Paul the truth about the outside world, he is forced to remain a prisoner. Trapped not only literally but creatively, Paul shares his latest novel with Annie as a thank you gesture - a book in which he has crucially chosen to kill off her treasured Misery. This is met with an outpouring of extreme rage by Annie who forces Paul into burning his work before demanding this is replaced with a version she approves of.

In one of the film’s many echoes of Hitchcock’s Psycho, Reiner shows us a man who is caught in not just one, but many traps. As a writer, seeing Paul’s creative isolation and entrapment is more painful than the hobbling scene as I experience these fears in continuous cycles myself on a regular basis. Paul survives the trauma inflicted upon him by Annie, yet the emotional scars are still present. Although the aftermath of his ordeal is visible when he has an alarmed reaction upon believing he sees Annie in a restaurant, this soon passes as he shrugs it off with a smile, showing that he is learning to balance both carrying and coping with his real-life nightmare.

The negative thought patterns, doubts and insecurities I grapple with on a daily basis make me feel detached and alone from others. In turn, my anxiety holds me trapped in poisonous cycles of self-loathing and uncertainty. These themes echo throughout the adaptations discussed here–in Carrie White’s loneliness and in Wendy Torrance’s imprisonment. As a writer, creative anxiety brings a mixture of pressure and guilt and therefore I find it highly therapeutic to watch Paul Sheldon emerge from his literal and metaphorical demons–although scarred–with the courage and self-belief to keep on writing. The motif of stuckness is also one that speaks to me personally–seeing Carrie sent to the closet, Wendy navigating the corridors of The Overlook and Paul confined to the restrictions of his bed reflects the way in which my anxiety holds me captive. What I see in these films are symbolic representations of the mental health struggles I endure and returning to them is always a calming and affirming experience that–at least momentarily–soothes me.

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] Oscar Nominations 2026: Where to stream all the horror picks](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769113319180-4INRRNMZK4DZLHRSUXX5/rev-1-GRC-TT-0026r_High_Res_JPEG-1024x372.jpeg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

Ahead of the Academy Awards ceremony, Ghouls has rounded up where you can stream all of the 2025 horror releases in the UK and the US from the comfort of your own home.