[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)

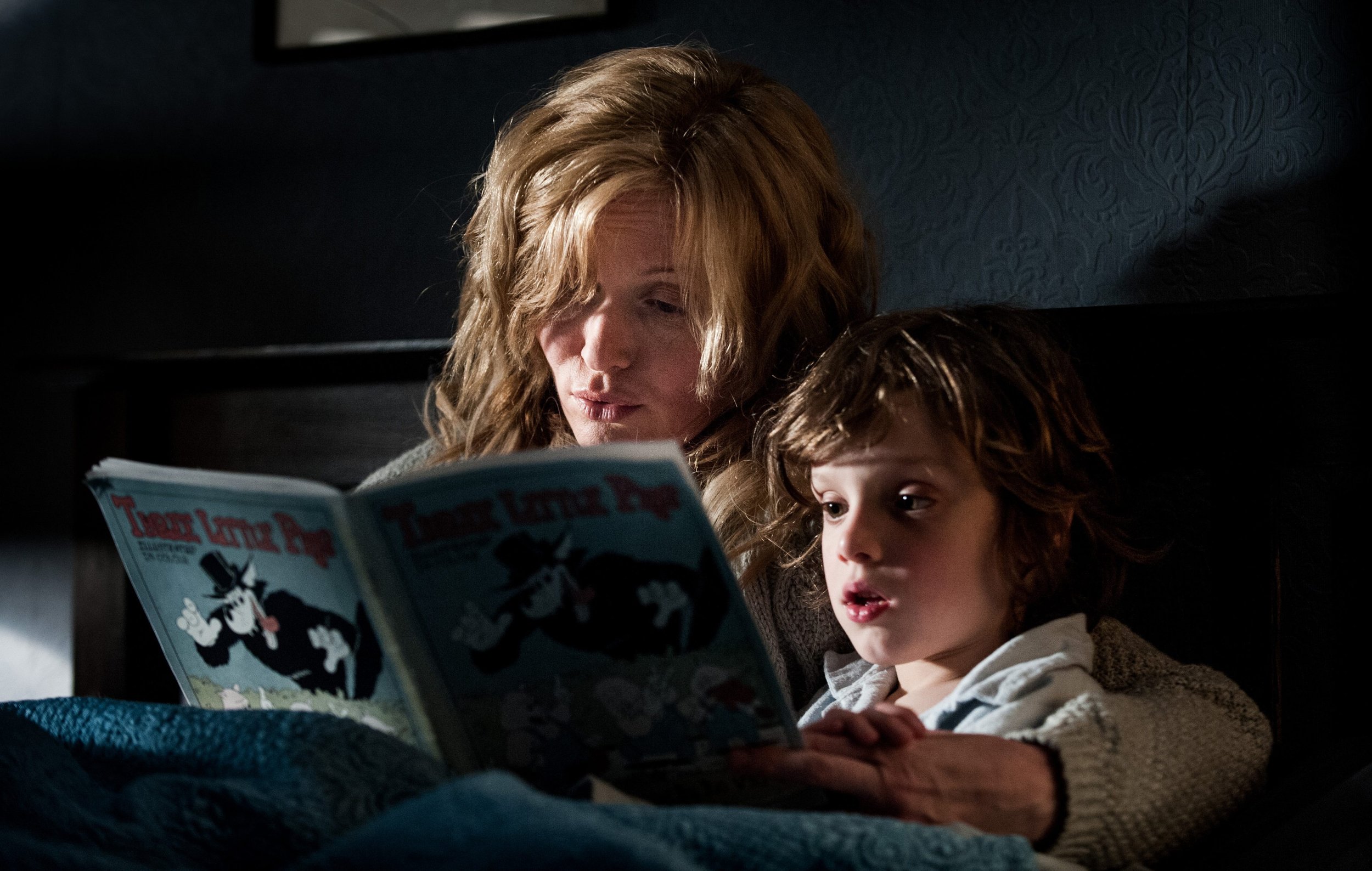

The Babadook is a 2014 psychological horror, the directorial debut of Jennifer Kent. The film centres on the painful relationship between Amelia and her son Samuel, following the death of her husband. When a copy of Mister Babadook, a pop-up book that grows increasingly sinister with each turn of the page, arrives uninvited, Amelia unwittingly summons a dangerous presence that will threaten not only their sanity but also their lives.

According to Kent “I wanted to create a myth in a domestic setting. And even though it happened to be in some strange suburb in Australia somewhere, it could have been anywhere.” Kent achieves this universality through her creation of realistic, complex characters and the themes of grief and loss that are central to the film. The protagonist, Amelia, is a complex, multi-layered woman. This stems from both Kent’s writing and directorial ability and the acting skills of Essie Davis, who brings a raw, almost frenzied intensity to the role. The power of Amelia’s character comes from her refusal to conform to what is expected of her. Throughout the film we see her refusing to compartmentalise her grief and sadness to suit others, leading to her continued ostracization and alienation from those around her.

Amelia’s real crime is that she is breaking the rules, she's still sad and unable to move on, much to the irritation of those around her and she's so angry that she's threatening. She refuses to play to the narrative that her world and wellbeing is centred on, and sustained by- motherhood. She doesn’t like Samuel at times, though she loves him, because he is the constant reminder of her loss. This doesn’t make for much of a ‘yummy mummy’ and so she’s left on the side-lines, to watch her son face the same alienation because he’s weird, he’s morbid and he’s strange. The overwhelming lack of sympathy from those around Amelia and Samuel adds another element of horror, that their sadness makes them so unpalatable shines a light on how society treats grief, and how we police sadness.

GHOULS PODCAST

Visually, Kent plays with light and dark, crafting a gloomy, haunted house aesthetic, with Amelia and Sam existing as two frail figures in a sombre grey house, living on just enough sustenance to survive. Alongside this saturation of grey, Kent uses elements of body horror, specifically physical trauma, as a means to externalise internal pain. Amelia finding glass in her soup is an apt metaphor for the cutting resentment she feels at having to care for her husband's murderer. Her toothache is a constant buzzing reminder of her heartache. As we see towards the end of the film, the only way to exorcise pain is to excise it, to cut it out and examine it. In Amelia’s case, this starts with a molar, and ends with the Babadook.

As Alexander Juhasz, designer of the film notes the Babadook is a complex, multifaceted character in his own right. He is a monster playing at being human, giving an approximation of what a man looks like, with his fixed, rictus grin and top hat. In this way, he is the dark half of Ameilia, who, for most of the film, is playing at being a mother who is coping with her loss. But, as Juhasz points out, he is also a “dark manifestation of repressed human emotions”, and it is in this capacity that we can understand Kent’s central theme of grief. He is all Amelia and Samuel’s darkness and pain made animate and terrifying. Every knock on the wardrobe, every sinister shadow, all shake loose more of these repressed feelings of anger, grief and sadness.

Kent also plays with the trope of the unreliable narrator; we are unsure for much of the film if the Babadook is real, or imagined, or if Amelia, or Samuel, are the architects of the increasingly ominous acts that surround them. This leads Amelia to question her own sanity, and gives the Babadook his way into her psyche. Amelia’s weakness is her refusal to let go of her grief, to move into acceptance of her husband’s death and let go of the rage she is nursing, closer to her than her own son. This weakness is exploited, in increasingly disturbing ways, and it is only by overcoming these emotional demons that she can vanquish their physical manifestation in the form of the Babadook. However, the Babadook is a very necessary evil. Through his torment, his terrorising and his relentless attempts to break Amelia and Samuel, he acts as the catharsis needed to push them out of the grey, endless stasis of their sadness, to move them back into the light and the world of the living. This is evoked starkly in the contrast with the greys and blacks of the majority of the film, and the sunny bright day we find Amelia and Samuel in at the closing scene.

The Babadook is a complex ode to grief, with Amelia trapped in her anger at the start of the film. Her resentment towards Samuel, towards life in general, has slowly eroded her sense of self, and she is trapped in a cycle of misery and sorrow. The arrival of the Babadook allows Amelia to break this cycle and provides an opportunity for Amelia and Samuel to unite to defeat a common enemy. This allows them to overcome their shared grief, and for Amelia to break down the walls she has built between herself and her son. The Babdook has a happy ending but one that is rooted in the realism of loss. The Babadook does not disappear, he shrinks, as sorrow does, and Amelia is able to manage him, by keeping him fed. The worms he feeds on are a visual metaphor for the breadcrumbs of memory that sustain all of us following the loss of a loved one. We can never vanquish our own personal Babadook's completely, because the purpose they serve is to allow us to remember the love we had that makes the loss so great. In this ending Kent reminds us that, as Nick Cave puts it, “grief is the terrible reminder of the depths of our love and, like love, grief is non-negotiable.”

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] Oscar Nominations 2026: Where to stream all the horror picks](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769113319180-4INRRNMZK4DZLHRSUXX5/rev-1-GRC-TT-0026r_High_Res_JPEG-1024x372.jpeg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

Possessor is a slick futuristic thriller in which Tasya Vos, an assassin for hire, must manage her responsibilities as an elite killing machine and complex feelings towards her husband and son, whilst taking on another high-profile job that will push her to the edge of her sanity.